Our healthcare standards have certainly come along way since the 18th century!

“The ways in which an academic medici were trained, examined, and licensed were still as varied as the way in which other healers acquired knowledge and legitimacy” (Duden, 1998, 53). Johann Storch was a male physician who created his path to a “doctorate” through his status, relationships, and a series of patchwork jobs and clients; however, titles such as a “doctorate” or “licentiate” at this time could also be bought rather than acquired through a university so it was quite an unregulated field and highlights how this lack of uniformity created “tensions between the academic self-image and a craftlike, practical competence” (Duden, 1998, 54). Storch obtained a university licentiate and built his clientele by serving the lower class citizens and seizing opportunities to move up the social scale over time.

He kept a logbook of sorts where he made notes about the patients that he seen, where he saw then, what their symptoms were, and what was prescribed. His records indicate that he interacted with his clients in the form of letters, house calls, third party representatives (such as a husband, father, brother, friend, etc.) and conversations.

What constituted the “modern body” in the 18th century? Well, according to Weisner, the body was considered to be irrational and functioned and looked differently for everyone. So when a client would go to a doctor seeking medical advice for ailments, there were several factors that were taken into consideration:

- Who are you?

(Noblewoman, laborer, prostitute, servant, etc.) - Marital status – yes this was something that would help determine what was causing your ailments!

- Are you young or old?

Many self-diagnosed and “these women frequently know what was wrong with them and tried to obtain the necessary remedies of their own, without recourse to a legitimate healer” (Duden, 1998, 74) and seeking help from a physician was likely the last option that would be explored and even then it was really just a way for the patient to confirm their self-diagnosis. The records also indicate that many of the women Storch seen were “older”, pregnant, birthing women, nursing, or in confinement, and it would appear that many would seek the advice of other women with experience before they came to Storch.

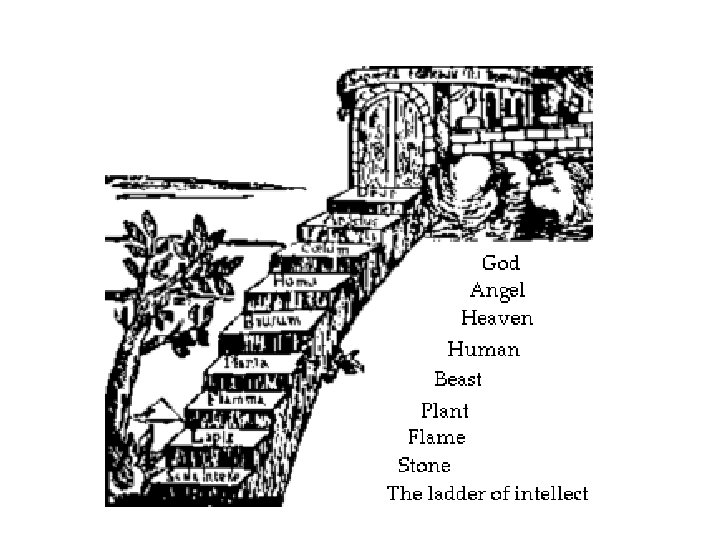

Pain is historically constructed across time and “Recent studies have shown that healthcare providers are more likely to perceive women’s expressions of pain and other symptoms as exaggerations. Women are also statistically more likely to have their pain dismissed as emotional or psychological than to be referred for further diagnostic investigations” (Cleghorn, 2021). In the 18th century, pain was perceived as not being a marker that needed to be examined by a Doctor. Pain was inflicted by God to punish those who sinned, and so people just endured it because it was “Gods will” and he was the highest authority on the “Great Chain of Being”; therefore, enduring pain inflicted upon you by God demonstrated you were “suffering” for your sinful ways.

The world of medicine and how we perceive pain has come a long way, but the complexities of a relationship between a doctor and patient is still relevant today.

References

- Cleghorn, Elinor. “The Gender Pain Gap: Perceptions of Women’s Health through History.” HistoryExtra, August 26, 2021. https://www.historyextra.com/period/victorian/gender-pain-gap-history-womens-health/.

- Duden, Barbara. “Chapters 2 and 3.” Essay. In The Women beneath the Skin: A Doctor’s Patients in Eighteenth-Century Germany, 49–103. Harvard University Press, 1998.

- The Great Chain of Being. Accessed December 13, 2021. https://the-great-chain-of-being-hamlet.weebly.com/visual.html.

- Wiesner, Merry E. Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2019. 63-107.