When the Western Roman Empire fell, the greco-roman world entered a period known as the “Dark Ages” where much of the medical texts were lost; however, thanks to the Islamic communities in the East, the culture of philosophers such as Hippocrates was kept alive vis-a-vie the Arabic translations of such works.

Hippocrates was a Greek physician in Pericles who is considered to be one of (if not the most) influential figures in the history of medicine and is known as the “Father of Medicine“.

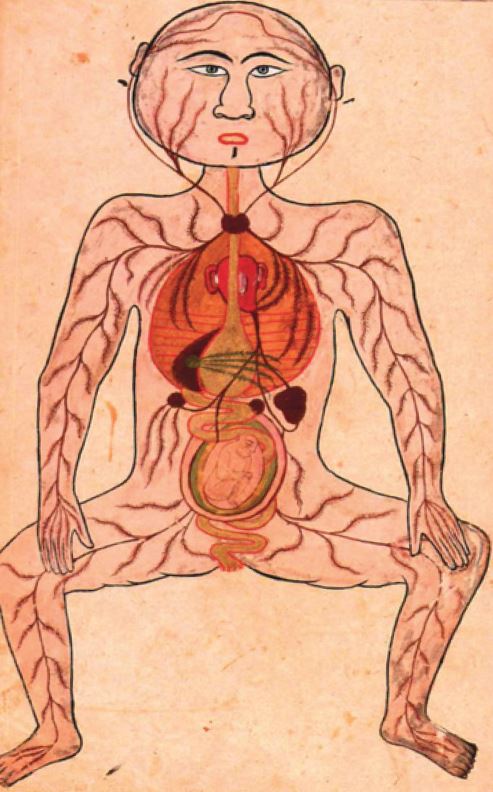

Hippocrates divorced religion from the art of healing and began strictly practicing medicine through scientific observations, practices, and applications of his experiences. He attributed illness to the imbalance of internal and external factors as follows:

4 Humors and their elements:

Blood = Air (hot/wet)

Phlegm = Water (cold/wet)

Black Bile = Earth (cold/dry)

Yellow Bile = Fire (hot/dry)

With this advancement in a more scientific approach to medicine, the notion of living a healthy lifestyle as a preventative to illness becomes more prevalent, and this is something we still live by today.

After the fall of the Roman empire, the field of medicine shifts again. In the western provinces illness becomes associated with religion again, and now those who become ill are perceived as suffering from divine retribution for their sins. Because the surviving medical texts were preserved in monastic spaces, only elite church clergy had access to them; however, in the eastern Islamic provinces, many of the Greco-Roman medical texts that they acquired were being translated into Syrian, Persian and Arabic languages during the “Golden Age of Islam” which lead to a thirst for more medical knowledge and we begin seeing rise in texts being created and eventually universities begin teaching medicine. The university of Salerno was the “Bridge” between the developing medicine in the West and the classically derived medicine of the East.

But where do women fit into all of this?

Well, women had been providing invisible healthcare for centuries in the home. Many mothers would act as a healer for her family through cooking or use of herbal remedies. So, women had been working as midwives and healers in their communities as well and held a number of positions including cunning women (who were most likely to be accused of witchcraft), herbalists, lying-in maids (birthing attendants), midwives, and even in some areas they could be health inspectors for the city.

According to Green, midwifery was framed as being in a rivalry with male midwives and “men (or rather literate men) ‘took over’ many aspects of women’s medicine – especially fertility concerns, which very often broadened into concerns with all aspects of the functioning of the reproductive organs”; this was because of the patriarchal systems that governed this field. Women were allowed to routinely attend to pregnant women and uncomplicated births because these weren’t seen as medical conditions. Midwifery was becoming increasingly more regulated in early modern Europe, and we see a rise in midwives being forced by the church to become licensed to practice, but having a license didn’t make a midwives more desirable to hire over an unlicensed one so this demonstrated the need for men to assert their dominance over women and keep them under their control.

With the invention of the forceps for example, we see the patriarchal system further oppressing women and their ability to work in the midwifery profession as there was a patent on this instrument that stated that women were not allowed to use it; therefore, if a baby was in the wrong position during birth a male physician/ obstetrician would have to be called in to complete the birth because they had the ability to use these tools.

What is even more interesting is that although the medical field was becoming more and more male dominated by the 18th century, many male physicians acknowledged that midwives did have a role to play in the birthing experience even if it was more just a social and emotional supportive one. and they performed many duties that midwives today still perform.

In Thomas’s article Early Modern Midwifery: Splitting the Profession, Connecting the History he discusses the benefits of the midwife during the birthing stage and says that “Midwives might help prepare the mother for birth by stretching her labia, checking and palpating the cervix, and lubricating the birth canal” and a “good midwife made labor less painful, moved it along more quickly, and could be the difference between life and death”.

The midwifery practice challenged the patriarchal hierarchies of early modern work and despite the efforts to suppress female midwives, many testimonials referred to midwifery as an “office” which was a term that was generally only held by men. It is deeply ironic how midwives evolve into this masculine gendered identity within their occupation. Although it might seem like this was a smart move on the part of female midwives, it in fact only opened this profession up further to male intervention which may be why today we don’t see as many midwives in the medical profession. Despite female midwives being a contested figure who lacked formal education, their informal knowledge of the female body helped them carve out space in the now male-dominated field of medicine.

Without the Muslim “Bridge”, medicine would not have seen a resurgence of knowledge which pushed the field to advance and kept it alive as a discipline.

References:

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopedia. “Migration period.” Encyclopedia Britannica, March 23, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/event/Dark-Ages.

- Green, Monica H. “Gendering the History of Women’s Healthcare,” Gender and History Vol. 20 (2008): 487-518

- Samuel S. Thomas, “Early Modern Midwifery: Splitting the Profession, Connecting the History.” Journal of Social History Vol. 43 (2009): 115-138.

- The Bridge: How Islam Saved Western Medicine. Films On Demand. 1996. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=79284&xtid=8204.

- Wiesner, Merry E. Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2019. 92-99,128-130.

Interaktywne Artykuły

May 4, 2025 — 9:17 am

This piece is a perfect blend of intellect and heart. The ideas you present are complex, but you navigate them with such ease that it feels like you’re inviting the reader to walk alongside you, step by step, through a maze of thought and emotion. It’s the kind of writing that challenges you and comforts you all at once.